Bread-Salt - when salt is able to speed up fermentation Author Elena Zheleznyak,

🔗Did you know that salt can sometimes speed up fermentation? When I read about this, I was surprised, because it is generally believed that salt slows down the fermentation of dough. If you add a lot of it (more than 5% to the flour mass), then it will be obvious - the dough will not budge. But, if you add a much less noticeable amount (up to 0.5% to the mass of the entire dough / dough), then it will ripen faster than without salt at all. When bakers noticed this trick, they began to apply it in production when fermenting dough.

At the same time, salt has a significant effect on other properties of the dough.

At the same time, salt has a significant effect on other properties of the dough. It binds water, which means that when it gets into the dough, it makes it more elastic and taut, less sticky, and allows you to add additional water to the dough (salt can bind up to 5% of free water). Thanks to this, the finished bread has a greater volume and, by the way, does not stale longer, again, because the salt prevents the moisture from removing from the bread, that is, drying.

In addition, salt affects gluten., it strengthens it while limiting swelling. As you know, the main proteins that make up wheat gluten are glutein and gliadin. The first makes the dough elastic, rubbery, the second - pliable, sticky, stretchable. Together, they give wheat dough the unique ability to stretch and hold its shape, hold air, be fluffy and porous. So salt reduces the ability of "sticky" gliadin to dissolve in water, so that even a dough with a large amount of water can remain elastic and non-sticky, while, like a dough of medium consistency WITHOUT salt, it can mercilessly stick to your hands. This is especially true for weak flour, which is mainly sold in stores and is most often used for baking homemade bread (10.6% protein in it is the standard value).

To summarize, I will say that salt strengthens the "skeleton" of the dough, allowing it to maintain its shape during proofing and to inflate as much as possible during baking. But bread dough without salt has a weakened gluten, it easily settles, loses its airiness, ferments and overripes faster, spreads in the oven, so the bread turns out to be less fluffy. The crust of bread without salt is pale, because during fermentation, the yeast eats up all the sugars and, as a result, there is not enough sugar to brown the crust during baking.

I noticed how wonderful salt affects the dough., during kneading wheat bread. We are talking about a dough with a moisture content of about 65%, not very steep and not very wet, which should spin like a bun in the bread maker, without smearing or leaving traces. If you do not add salt at the beginning of the kneading, see how the dough will behave (this is in the middle of the batch).

It smears, clings to the walls, there is no question of a "kolobok". But look, I added salt 10 minutes before the end of the batch.

After one or two minutes, the dough is perfect! Completely non-sticky, elastic, does not smear anywhere and does not cling. Please note that I did not add any additional flour, only the salt put according to the recipe. Such dough can be taken out of the bucket in one motion, picking up and pulling, it will pull itself up and gather, leaving no trace in the bucket. But the finished result is small baguettes.

For the purity of the experiment, I baked bread according to the same recipe, only without salt, with one loaf. During kneading, the dough was smeared with a mixer and stained the sides of the bucket. I just couldn't get it, I had to literally pick it out, because it was terribly sticky.Look at my hands and how much dough has stuck to the sides and bottom.

Despite 20 minutes of kneading in a bread maker, the dough remained sticky, which is very difficult to work with. In textbooks they write that this happens with a dough made of weak flour, without salt it completely "unsticks" and stains everything it touches. This is due to the effect on the protein of the enzyme of flour protease, which, without the presence of salt in the dough, decomposes the protein at an accelerated rate (this process is called proteolysis or enzymatic degradation of protein), which causes the dough to thin and stick. Salt to a certain extent neutralizes the effect of this enzyme, preventing the protein from swelling unnecessarily, and the dough to lose its elasticity and shape.

And here is the ready-made "salt-free" bread.

It blurred, parted, almost turned into a cake. Incidentally, I did not make incisions, it was he himself. The pores are beautiful, but characteristic, from them you can immediately determine that the gluten was weakened. These pores are very similar to those obtained with fruit yeast bread. He also has his own stories with gluten and the effect on it of fruit acids and enzymes, which causes it to break down, and the pores have such a characteristic shape.

To taste, bread without salt, to be honest, is not tasty, unleavened, flat, not bready, something is clearly missing, and not just salt, but aroma, taste, bouquet. Therefore, if there is no urgent need (for example, there are people who cannot eat salt for health reasons), it is better not to bake bread without salt.

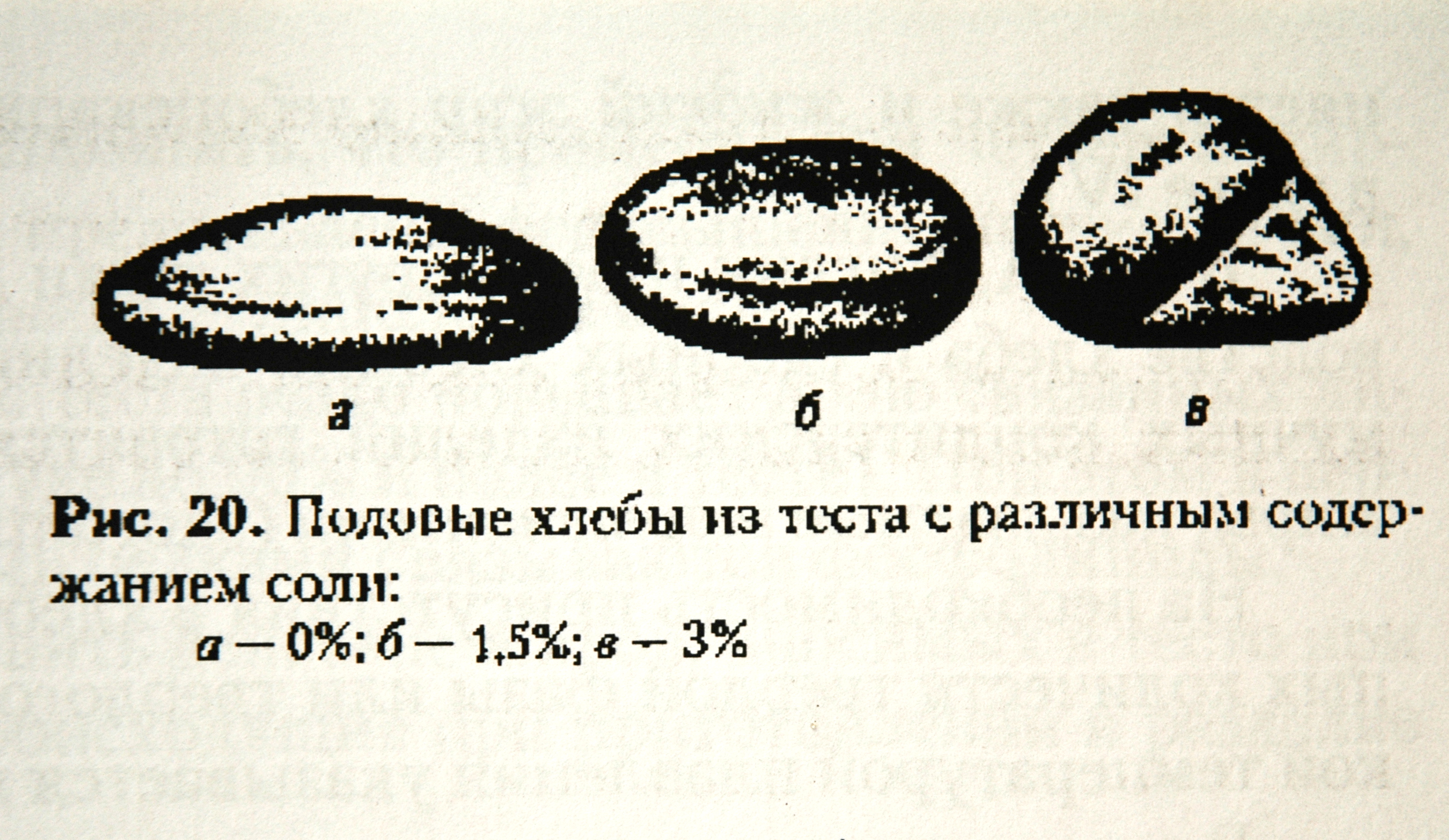

How much salt should be added so that the dough is good and the person tastes good? Professional bakers advise for every 100 gr. flour to take at least 1 and no more than 3 grams. salt, in percentage it is from 1.3 to 2.5% by weight of flour in the recipe. But what will happen if you put more salt in the dough? This illustration from Lev Auerman's book "Technology of bakery production" demonstrates well what will happen.

Look, on the left, bread baked without salt. During proofing and baking, the dough spread, the piece became flat, more like a cake. The middle option is bread with 1.5% salt. Lush, moderately tall, well-shaped. On the right is a bread with 3% salt, you can see that its volume is smaller, it seems that its crust broke during baking, because the dough did not have the required degree of elasticity and extensibility due to the high salt content.

Nevertheless, there are many different types of bread in the world, including very salty ones. The recipe for salty varieties provides for a delayed or gradual addition of salt: part is added together with the dough, part at the end of kneading or during fermentation, when the dough has reached the desired consistency and properties.

Then I had a little epiphany. If you remember, I once tried to bake bread-beret according to Sergey's recipe. There, in a recipe for 500 flour, there is 14 gr. salt, plus salt from fermented dough, which is almost 3%. I tried to bake and this bread seemed very salty to me, so in my attempts I reduced the salt to 10 grams. and had certain problems with kneading dough, molding, opening cuts. If you take a look at Sergey's blog and look at his Swiss bread, you will see that this is a characteristic feature of Swiss bread - a wet dough with a high salt content. Now I understand that this is, in fact, such a technique: to make wet dough “on the verge of spreading” elastic and easy to use, you need to add a little more salt to it. Of course, this is in addition to the fact that wet dough needs to be folded more often (at least 3 times per fermentation) and, ideally, to provide cold proofing or fermentation (that is, in the refrigerator).

When should you add salt to the dough? For me, this question was the most intricate. I often met the recommendation to add salt at the end of the kneading and, without much hesitation, added it at the end, when the dough was already, in fact, well kneaded, and in 3-5 minutes the salt had time to completely disperse so as not to crunch on the teeth.About why and why I do this (and do not add salt, for example, at the beginning of the kneading), I thought only after I noticed what happens to the dough after adding salt (see the photo above during the kneading process before adding salt and after). If it works such wonders, why not add it at the very beginning? In general, thinking about the reasons, I assumed this: salt makes the dough more elastic and "resistant" to kneading, without salt the dough is more elastic, therefore it is easier and faster to achieve the required degree of gluten development. Simply put, mixing is faster. It turns out that this recommendation was popular in production and for this very reason. There, the "bread" schedule, mixing speed and energy savings were and are of great importance. Judge for yourself: dough without salt is kneaded twice as fast as salted dough, hence the recommendation to add salt at the end of kneading.

At the same time, the French processor Raymond Calvel was categorically against the delayed addition of salt to the dough, explaining this by the fact that while the dough is being set or kneaded without salt, the protease decomposes the wheat protein at an accelerated rate, as a result of which the bread loses a large share of its flavor and aromatic potential. This also applies to the autolysis stage. If the maturation is short, no more than 15 minutes, salt can be added after autolysis, but if it is 30-60 minutes before, directly with mixing flour and water. If you are dealing with a recipe for very salty bread, like a Swiss one, then salt can be added gradually: a little with dough, a little during autolysis, so as not to greatly limit the swelling of gluten, and part at the end of the batch for similar reasons.

Now it's clear what the salt is