History of Olivier salad (method of its preparation and recipe)

Contrary to popular belief, the modern Olivier salad has little to do with what the French chef Lucien Olivier invented. Except, perhaps, the name itself. In the 19th century in Moscow, at the corner of Grachevskaya Street and Tsvetnoy Boulevard, the facade of Trubnaya Square was the three-storey Vnukov house, in the two upper floors of which there was a second-class tavern "Crimea", where the most notorious audience walked - from card sharpshooters and gigolos to poor merchants and visiting provincials. The basement of the building was occupied by the gloomy tavern "Hell", in which the most desperate Moscow thugs of that time celebrated their dark deeds. Opposite this gloomy building was a vast wasteland that belonged to some of the Popov brothers. At the very beginning of the 60s of the 19th century, the Frenchman Olivier acquired this entire wasteland from one of the Popov brothers, whom he met quite by accident - both bought bergamot snuff, to which they were great hunters, in one of the shops that densely populated the wasteland and a special income landowners who did not deliver.

Olivier by this time was already famous, he prepared exquisite dinners on orders at the homes of wealthy clients and managed to make a small capital. Olivier built on a vacant lot, demolishing shops and small inns, a palace of gluttony, a tavern "Hermitage", in which everything was in the French manner. In the "Hermitage" one could taste the same dishes that were previously served only in the mansions of noblemen. The inn served caviar and fruit in huge ice vases, carved in the form of fairytale palaces and various fantastic animals. The Hermitage immediately became a favorite place for the nobility. In fact, this tavern was, according to our modern concepts, an upscale restaurant for the elite. This institution employed a hundred people, of whom 32 were chefs. After an exquisite dinner at the Hermitage, it was considered particularly chic to go on reckless drivers to dinner at the Yar, where there is “gypsy-style” cold veal cooked in a special manner and listen to the Sokolovsky gypsy choir. By the way, the very word Hermitage had nothing to do with the St. Petersburg tsarist mansions. In the French language fashionable at that time, “Hermitage” meant a secluded corner, a hermit's dwelling. Often the owners jokingly called their country houses, estates, recreation pavilions that way (by analogy with how we now call our dachas hacienda).

At first, the Hermitage was run by three fellow countrymen: Olivier was in charge of the general management, Marius served the most important guests, and the kitchen was headed by the famous Parisian chef Dughet. Soon, the already very popular "Hermitage" acquired even greater fame among gourmets thanks to Monsieur Olivier's magnificent salad, distinguished by its delicate refined taste. And the invention of this dish happened, one might say, by chance, without much effort on the part of the future culinary genius. In French cuisine of that time, the ingredients of the salad, as a rule, were not mixed - the ingredients were beautifully laid out on a platter or laid out in layers. (In general, French cuisine until the beginning of the 19th century was poor for snacks and a lot of French culinary experts drew precisely from the Russian gastronomic tradition. At least, for example, the Russian order of serving dishes - first, second, third.In Europe, it was customary to put everything on the table at once, or to change dishes, especially not observing the division into main, secondary and snacks. Each eater ate what and when his soul desired). Initially, Monsieur Olivier treated customers to a similar salad, consisting of separately laid out products and called game mayonnaise. Moreover, Olivier came up with a special sauce for this dish based on olive oil, vinegar and egg yolks. This sauce was named by the inventor of Provençal.

There is a legend about how this sauce was invented: Olivier ordered one of his chefs to prepare a traditional French mustard sauce for one of the dishes, which, along with mustard, includes butter, vinegar and pounded yolks of boiled eggs. However, either by mistake, or deciding to save time, the cook added raw yolks to the mixture. The result of his creativity amazed the owner - the sauce turned out to be unusually lush and surprisingly pleasant to the taste. Having found out the reason for such a strange transformation of the mixture and giving the negligent cook a scolding for order, Olivier realized that the chance helped him create a completely new sauce that could radically improve the taste of any dish. Over time, the mayonnaise dish itself disappeared from Russian cuisine, and the sauce invented for it remained. And now, by the word Provencal mayonnaise, we mean exactly this original sauce, and not the salad for which it was invented by a French cook.

Game mayonnaise was prepared using a rather complicated technology. Fillet of hazel grouse and partridge were boiled. Jelly was made from the broth in which the bird was boiled. Poultry slices were placed on a dish with mayonnaise sauce, diced jelly was placed between them, and potato salad with pickled small cucumbers, in other words, gherkins, was poured in a heap in the center. All this was decorated with halves of boiled eggs. However, to the surprise and, perhaps, to the displeasure of the chef-artist, tipsy Russian connoisseurs of beauty, not wanting to taste the served dish in layers, as it was supposed to, barbarously stirred everything into porridge with a spoon and ate this mush with pleasure. Yet, apparently, Lucien Olivier was not a fool and did not try to swim against the current, convincing his guests to eat as it should be. He decided to just follow the tastes of the local public and immediately began to cut all the mayonnaise ingredients into small cubes and mix it all before serving, at the same time adding some more ingredients popular with visitors.

Thus, Olivier actually became the inventor of a new salad against his will. This salad initially gained fame among the Moscow public under the name French, although it had practically nothing to do with French cuisine. Moreover, abroad he is still more often called Russian. Lucien Olivier kept the exact method of preparing the salad in the strictest confidence even from his partners Marius and Duguet and always prepared it only himself. With the death of the famous chef, the secret of his recipe was lost. He did not consider it necessary to pass it on to anyone. And soon the Hermitage itself passed from Marius to the possession of the furniture maker Polikarpov, the fishmonger Mochalov, the barman Dmitriev and the merchant Yudin, who organized the Olivier partnership. The institution became known as the "Big Hermitage". The public of the inn has also changed. The aristocrats, large landowners who were previously regulars of the inn, after the reform of 1861, quickly ate their ransom money and became impoverished. The “new Russians” of that era moved into the “Hermitage” - the rich merchants and prosperous intelligentsia, doctors, lawyers, and successful journalists who took a bite of the reforms of Alexander III (including the famous Gilyarovsky, who more than once mentioned the “Hermitage” in his articles) ... This public was able to shift most of the money that ended up in the hands of the landowners who suddenly lost their land into their pockets. Their requests were simpler, and their tastes were more vulgar.But they also wanted to taste the famous Olivier, posing as aristocrats, in fact, being, for the most part, ordinary rogues.

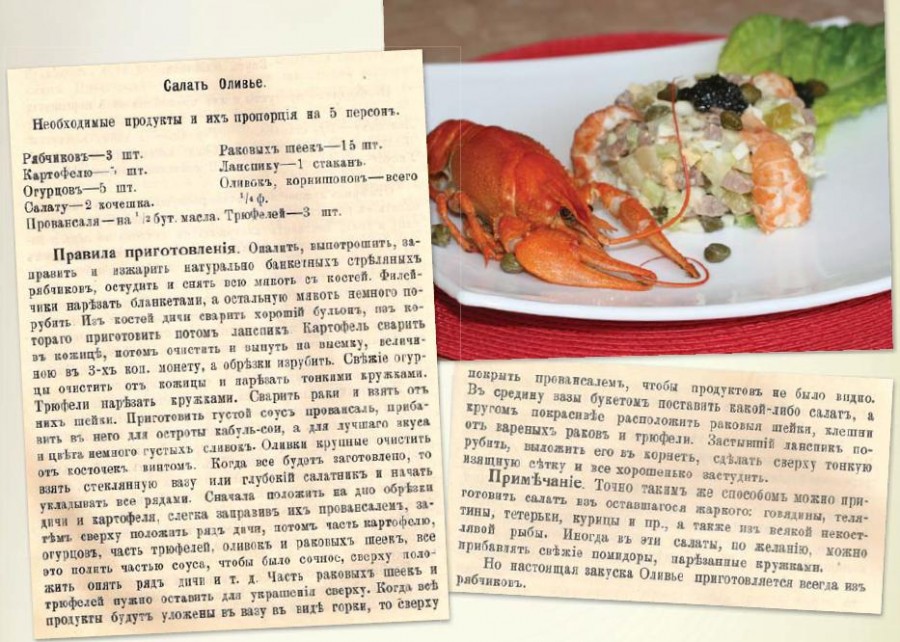

Despite the fact that the secret of the authentic salad was lost, all its main ingredients were known. Until the very closing of the Hermitage, a salad called Olivier was served there, but, according to the reviews of visitors who still remembered the true Olivier, the taste was completely different. There have been many imitations and attempts to reproduce the famous dish. But when preparing a dish, it is not even the recipe itself that is important, but the technology of its preparation, as well as, possibly, the use of some “secret” ingredients. So the main secret - the reconstruction of the real Olivier was not solved. For example, in the cookbook "Culinary Art" for 1899, the following recipe for Olivier salad was given: breasts from three boiled hazel grouses, 15 boiled crayfish necks, five boiled potatoes, one glass of lanspik, five pickled cucumbers, to taste capers, olives, gherkins, Provencal oils, three truffles. All this is cut into pieces and poured with a lot of mayonnaise and soy-kabul sauce.

The new owners of the Hermitage at the beginning of the 20th century reproduced the salad recipe as best they could. This version of Olivier included: 2 hazel grouse, veal tongue, a quarter pound pressed caviar, half a pound fresh salad, 25 boiled crayfish, half a can of pickles, half a can of soybean cabul, two fresh cucumbers, a quarter of a pound of capers, 5 hard-boiled eggs and, of course, mayonnaise sauce. However, according to reviews of people who still remembered that real Olivier, the taste was still different. It is worth giving an explanation to these recipes: lanspeak is a kind of jelly made from veal legs and heads with many spices. Soy-kabul is a kind of rather spicy, popular in those distant times, soybean-based sauce. Pikuli are pickled (pickled) small vegetables, at least the same cucumbers.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a new stream of eaters poured into the ranks of the restaurant's visitors, even less demanding, less sophisticated and demanding - shopkeepers, actors, folk poets and writers of various kinds, who, although not even the intelligentsia by origin, nevertheless, wanted to look the same aristocrats (as they understood it). Of course, they would not defend their honor with a pistol or a sword in hand, but they were not very fools to eat “aristocratic”. This concludes the first, pre-revolutionary stage in the history of this wonderful dish.

In 1917 the Hermitage was closed. The World War and the two Russian revolutions that crowned it almost completely destroyed both French chefs and Moscow connoisseurs of their art. Grouse with partridges has become simply dangerous not only to eat, but also to mention them, since a picky eater could be considered a bourgeois and just plop in the nearest gateway. It seemed that not only Monsieur Olivier's secret had been hopelessly lost, but the very idea of such a dish, alien to a new society emerging in torment (in the literal sense of the word), was doomed to oblivion.

But a cheerful NEP came. The Hermitage reopened its doors, but the audience in it was already completely different - another wave of crooks who suddenly got rich, but who got rich not on the rapid economic growth, not on their personal popularity, not on their talent, but on hunger and ruin. Even the former rootless merchants and actors, in comparison with them, looked like true aristocrats (By the way, it is this audience that our grandfathers and grandmothers recall with nostalgia, confident that they found those real aristocrats in their youth). Olivier salad has reappeared on the menu. But he had little in common even with the pre-revolutionary one. The Napman Hermitage did not last long, and in 1923 it was also closed, and the Peasant House was opened in its premises. It had a dining room on the menu with no salads at all. Now in this house 14 on Petrovsky Boulevard, at the corner of Neglinnaya Street, a publishing house and a theater are located.However, in the new, Soviet, society, the structure of which is finally taking shape by the end of the twenties, its own new elite appears, which also needs its own new, albeit based on something that came from the past, attributes. Including culinary. Many still well remembered the glory of the old Moscow, St. Petersburg, Nizhny Novgorod, Rostov, Odessa restaurants.

New Olivier-Stolichny (aka Moscow, aka Meat, aka Summer)In the early thirties, Ivan Mikhailovich Ivanov remembered the once famous Olivier, the chef of the Moscow restaurant, who, according to him, served in his youth as an apprentice for Olivier himself. He then became the true parent of the Olivier salad we know. In Soviet times, the Moskva restaurant was almost an official guest house, a kind of Kremlin branch for the most important persons of the state. And, it is no coincidence that it is in it that the Soviet culinary art reaches its peak. Ivanov replaced the ideologically unrestrained hazel grouse with a worker-peasant chicken, threw out all kinds of incomprehensible rubbish like capers and pickles, and called his creation -

salad "Capital"... Moreover, the gourmets who miraculously survived from the bourgeois times, who ate the true Olivier, allegedly even assured of the perfect identity of the tastes of the old and new versions. But let's leave it on their conscience.

The secret of New Olivier-Stolichny (aka Moscow, aka Meat, aka Summer), Chef Ivanov is quite simple and

consists in the strict equality of the weight parts of its constituent components: chicken meat, potatoes, pickled gherkins (or cucumbers), boiled eggs. Green peas are put in half the rest of the ingredients. Canned crab meat is added and the whole thing is poured with mayonnaise. Salad ready. The recipe should not contain any sour cream, carrots or onions.Modern salad OlivierOn the vast expanses of the Union in numerous points of the Public catering, within the framework of the general democratization of society, the dish immediately began to be even more democratized. The main component in Stolichnoye was potatoes, which were actively introduced at that time and replaced various cereals in the diet of Soviet people. Already not even hazel grouses, but chicken, began to be replaced with ham, boiled meat, and then they completely reached the logical point of idiocy, decisively rejecting any natural meat in favor of a certain average doctor's sausage. Delicate pickled pickles have transformed into vulgar pickles. Salads “Moscow”, “Capital”, “Russian salad”, “Meat”, vegetable salad with meat, vegetable salad with hazel grouse, vegetable salad with meat and hazel grouse, all these are restaurant varieties of our friend - “Olivier”. Neither Olivier himself nor Ivanov has ever had boiled carrots in the Olivier recipe. There is a legend about how it appeared in some recipes: in the thirties, in the restaurant of the Moscow House of Writers, according to the testimony of the poet Mikhail Svetlov, a resourceful local chef, instead of expensive crabs, relied on by the recipe, began to put finely chopped carrots, in the hope of that drunken masters of the pen simply cannot distinguish red carrot shavings from pieces of a torn crab body. Of course, the progressive leaders of the knife and scoops throughout the country quickly took up this initiative and expelled the crab from the folk salad, becoming quite official to chop carrots into it.

In the forties, immediately after the end of the Second World War, in the wake of the liberal mentality brought back from Europe by the soldiers who returned from Europe, visiting restaurants became quite common for a very wide audience. Everyone wanted to live and enjoy life not someday, but right here and now. It was then that a successful and inexpensive snack began its new triumphant attack on Soviet restaurants.

And in the fifties "Stolichny" firmly took a leading position in the restaurant kitchen, pushing the eternal Russian vinaigrette to second place on the festive table.Lettuce acquired wide popularity in all layers of the Russian (it should be clarified - it is the Russian, not the entire Soviet) people in the 60-70s of the 20th century. It was then that he left the restaurant kitchen and settled in the communal one. Before that, "Olivier", of course, was famous, but the audience of fans was much narrower - mainly the intelligentsia and responsible party and Soviet workers who loved to while away their free time in a restaurant. During these years, people finally begin to live in greater prosperity. They have a desire, and, most importantly, an opportunity arises to diversify their menu somewhat, even if only for the time being only a festive one.

In the suddenly surging period of the Khrushchev thaw, the salad was so popular that, as usual, the leaders wanted to lead the popular movement here and lead the close ranks of Soviet eaters behind them, inventing the loyal name “Soviet” for everyone's favorite dish. How beautiful it would be - on New Year's Eve all Soviet people ate Soviet salad and washed it down with Soviet champagne! Handsomely! And ideologically sustained. But the top, together with the new-old salad, which they renamed in the menu of canteens of administrative institutions, went their own way, and the salad remained in the minds of the masses under its proud overseas label - "Olivier". ... ...

And now - the main secret of this dish - the French monsieur Olivier never invented our native Russian salad Olivier! ... ... ... How so!? Yes, just in Soviet times, the name of a dish widely known in peasant Russia was replaced by a beautiful, foreign, famous one. Our Olivier is nothing more than a salad for okroshka (potatoes, herbs, onions, meat, eggs, cucumbers), which they often ate without diluting kvass, but simply pouring sour cream. Not for nothing that many people still prefer to pour our Olivier not with mayonnaise, but with sour cream! This is the reason, surprising to many, the difference between modern Olivier and the "real" one. And the whole world eats ours, and not Monsieur Olivier's, salad, mistakenly still attributing to him the honor of his invention. At the same time, still trying to assure us that we are eating some kind of plebeian version of the famous dish. It is interesting that those who tried to make Olivier according to those “real” recipes were extremely disappointed with his taste - it’s not the same, not native! Boring. To this day, foreign Russian restaurants allegedly serve as a real Olivier, but, according to the reviews of our compatriots who have tasted this aristocratic dish, this is not at all the Olivier that we love and know. Much worse. (Here, by the way, is another example of the influence of French culinary experts on Russian cuisine, which indirectly confirms what has been said: the primordially Russian appetizer from beets, known in Russia since pre-Petrine times, we suddenly began to call the French word vinaigrette, from the French word meaning vinegar, and count its also a French dish.At the same time, in France itself this dish is called salad de ruesse.It's good at least that we did not have a French culinary specialist by the name of Vinaigrette to appropriate the invention of this salad. completely different dishes, Olivier and our Olivier, brought together in our minds into a single whole by the will of a historical event - the desire of our own Soviet intelligentsia to be at least somewhat closer to those old Russian intellectuals. At least eat the same thing. So someone pasted the famous name, either as a joke or seriously, to a popular salad adapted for restaurant cuisine by I.M. Ivanov. Or maybe just at a certain stage, the word Olivier itself was associated among the people with the word salad, a dish that was completely uncharacteristic of the native Russian cuisine and was used mainly only in the aristocratic environment. In the middle of the 20th century, the phrase salad Olivier, united in our minds, was fixed for a natural Russian snack. basis for okroshka. The great undoubted merit of the Frenchman Olivier consists only in the fact that he introduced dishes of this type into Russian folk cuisine, enriching it with the very concept of salad.You will not find a recipe for Olivier salad in any modern solid culinary reference. Nobody knows the recipe of the real Olivier, and no one, formally, has the right to call this name a dish that is not prepared according to the recipe for which it should be prepared. The author, having rest in Bose, took with him there the recipe for making his salad. What was allegedly restored using known ingredients, strictly speaking, is not the famous cook's Olivier salad.

Olivier expiry date After a New Year's dinner, there is often a lot of food left, which was fed to the guests. When creating Olivier, you need to consider its shelf life so that you can enjoy it the next day. A typical classic salad, which many people eat for a holiday, can stand in the refrigerator for up to 40 hours, provided that the ingredients are not seasoned with mayonnaise and salt. Under other circumstances, it is not recommended to keep Olivier for more than five to six hours. Season the treat right before serving, or leave some without sauce in the fridge to serve fresh or later.

Can I freeze salad If you want to keep Olivier longer, you can try freezing it. Only the salad that has not been seasoned is suitable for freezing, otherwise all the ingredients will turn into a shapeless mass and lose their taste. It is not recommended to freeze the appetizer with fresh cucumbers. How to do it: put the ingredients in a bag, put them in the freezer. Shake occasionally (1-2 times during the first hour of freezing) so that the components of the dish are scattered. Defrost the salad exclusively in the refrigerator, transferring it to the zero compartment from the freezer.

Ingredients for the correct proportions of a snack (per serving):

forty-five grams of doctoral sausage;

20 grams of cucumbers;

fifty grams of potatoes;

20 grams of canned peas;

1 chicken egg;

thirty grams of mayonnaise;

1/8 part of a medium onion;

five grams of parsley, dill;

salt to taste.

Bon Appetit!