|

The commander of the French expeditionary force on the island of Haiti, General Leclerc, was looking for a large detachment of soldiers who went into the interior of the island, but soon stopped giving any news of themselves. The commander of the French expeditionary force on the island of Haiti, General Leclerc, was looking for a large detachment of soldiers who went into the interior of the island, but soon stopped giving any news of themselves.

In the flowering valley, the general and his retinue finally saw the missing regiment camped. The signal sounded - no one answered. The enraged general burst into one of the tents, grabbed the sleeping sentry by the shoulder and saw the yellow-blue face of the dead man. The eight thousandth detachment of Napoleonic soldiers was destroyed with amazing speed by the deadly yellow fever virus.

... Viruses are the smallest of living things. Viruses can breed even inside bacteria. They have collected a terrible tribute from millions of human lives and still threaten people. This threat will persist until new radical means put an end to the power of viruses.

Perhaps this agent will be interferon.

The so-called viral interference has been known to scientists for quite some time. A virus that has infected living tissue prevents other viruses from multiplying in it. For example, if the tissue is infected with the yellow fever virus, then it is not possible to infect it with the influenza virus, no matter how much it is administered. The virus that infected the tissue first, as it were, "locks the door" and hangs a sign: "Busy."

But how he does it, remained a mystery until very recently. The mystery looked, perhaps, even more strange because even viruses killed by heat were able to "lock the door", that is, they prevented the tissue from infecting with viruses of a different type.

The British researchers Isaacs and Lindemann added heat-killed influenza viruses to the chicken embryo cell culture. It was unexpectedly found that the nutrient medium after such a procedure acquired an amazing property. If fresh cells of the embryo were introduced into this environment, after removing old cells, then it was no longer possible to infect them with either live influenza viruses or viruses of any other type. This means that the mysterious interference was due to the presence of some substance that appeared in the environment!

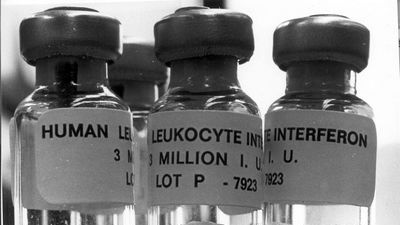

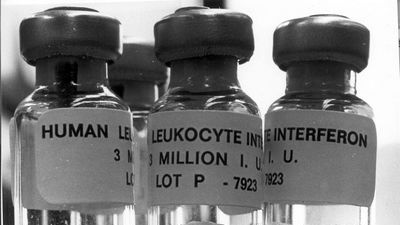

After painstaking work, this substance was isolated. It turned out to be a previously unknown protein. They called him interferon.

Interferon molecules are about the same size as the molecules of a well-known blood protein - hemoglobin. During viral infection, interferon molecules are produced in the body. Surprisingly, unlike all other proteins, interferon from one animal, administered to another, does not induce the formation of antibodies, which usually occurs when any foreign protein invades. Consequently, interferon, produced in the tissues of, say, a monkey, can protect human cells from the attack of various viruses.

Another striking feature in the behavior of interferon was also its complete inability to prevent the multiplication of viruses in cancer cells. Another striking feature in the behavior of interferon was also its complete inability to prevent the multiplication of viruses in cancer cells.

Interferon “refuses” to protect “bad” cancer cells. But in the same way, interferon “refuses” to protect the chicken embryo if it is younger than 8 days of age. These observations seem to hold the key to understanding the effects of interferon.

The virus is composed of nucleic acid and protein and can only reproduce inside living cells. The virus brings into the cell only its hereditary code written in the structure of the nucleic acid, and the "building materials" and "fuel" necessary for the manufacture of future viruses are taken from the cell itself. But cancer cells and embryonic cells in the early stages of development have one thing in common: to ensure their rapid growth, they produce in increased quantities the cell fuel - the famous adenositriphosphoric acid (ATP).

Therefore, the secret of the protective effect of interferon lies, apparently, in the fact that interferon interferes with the work or the appearance of ATP, which is necessary for the synthesis of new viruses. And in those cells - embryo or tumor - where ATP is in excess, interferon cannot have its protective effect against virus infection.

In laboratory experiments, interferon has already protected mice, rabbits and monkeys from viral infection. In the past year, 38 volunteers were injected. And only in six cases did interferon have no protective effect! Meanwhile, it was not known in what dose and in what way interferon should be administered. Therefore, the success of the first test is especially significant.

Of course, the widespread use of interferon will require many more solutions. But there is every reason to hope that over time, interferon will justify the wildest hopes of scientists.

N. Ivanov, A. Livanov, V. Fedchenko

|

The commander of the French expeditionary force on the island of Haiti, General Leclerc, was looking for a large detachment of soldiers who went into the interior of the island, but soon stopped giving any news of themselves.

The commander of the French expeditionary force on the island of Haiti, General Leclerc, was looking for a large detachment of soldiers who went into the interior of the island, but soon stopped giving any news of themselves. Another striking feature in the behavior of interferon was also its complete inability to prevent the multiplication of viruses in cancer cells.

Another striking feature in the behavior of interferon was also its complete inability to prevent the multiplication of viruses in cancer cells.