|

Flying fishes (family Exocoetidae), well known to everyone from the descriptions of sea voyages, are an integral part of the landscape of warm seas and are one of its most characteristic external manifestations. Flying fishes (family Exocoetidae), well known to everyone from the descriptions of sea voyages, are an integral part of the landscape of warm seas and are one of its most characteristic external manifestations.

In the ecosystem of tropical waters of the open ocean, flying fishes occupy a unique position, being the only massive planktophages that constantly inhabit the surface layers of the epipelagic zone (the upper layer of the water column).

The flying fish themselves constitute, in turn, an important component of the diet of predatory fish - coriphenes, snake mackerels, small tuna, as well as seabirds, squid and dolphins. In some areas (Japan, the Philippines, India, Polynesia, the islands of the Caribbean), a special fishery for flying fish is conducted, which, however, has only local significance, but gives, according to a rough estimate, at least 500 thousand centners annually. Flying fish are caught using gill nets, purse and fixed seines, cap nets and special traps and fishing rods; there are other methods based on the peculiarities of the ecology of these fish (in particular, on their positive reaction to artificial light and on spawning approaches to the shores).

Flying fish, as their name suggests, can fly through the air. Where does this ability come from? All representatives of the garfish order, which include flying fish and besides them, also half-fish, garfish and saury, inhabit the uppermost layers of the water. Many of them, when frightened or in pursuit of prey, can jump out of the water, sometimes making whole series of successive jumps, like a ricocheting stone. The improvement of these jumps led in the end to a gliding flight, allowing flying fish to escape from many predators, although, of course, not guaranteeing them complete safety: for example, a coriphene, having scared a flying fish, chases it under water and grabs it at the moment when it sinks into water. Nevertheless, the explanation of flight as a device for rescuing from predators is now generally accepted and has not been questioned for a long time. Another point of view is expressed by prof. V.D. Lebedev, who believes that forage migrations with the use of constant winds played a decisive role in the development of flight. It must be said, however, that the existence of long-distance migrations of flying fish in the tropical zone proper has not yet been proven. The available data, on the contrary, testify to the "sedentary" way of their life.

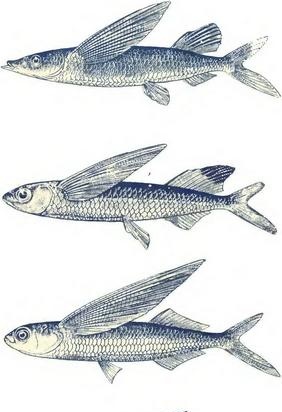

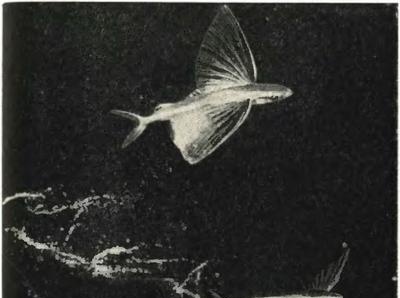

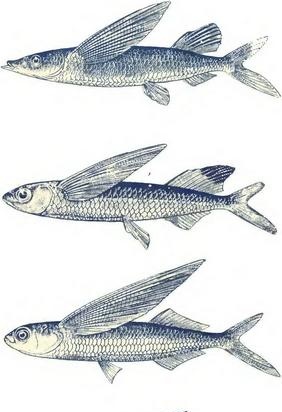

Flying fish are very diverse - the family includes 7 genera and about 60 species. The ability to fly is expressed to varying degrees in different genera. Flight of "primitive" flying fish from the genera Fodiafor and Parexocoetus, with relatively short pectoral fins, is less perfect than in fish with long "wings". The evolution of the flight of flying fish proceeded, apparently, in two directions. One of them led to the formation of the genus Exocoetus - "two-winged" flying fish using only pectoral fins in flight, which reach very large sizes in them (up to 80% of body length). Another direction is represented by "four-winged" flying fish (4 genera of the subfamily Cypselurinae — Proghichthys, Cypselurus, Cheilopogon, Hirundichthys, - combining about 50 species). The flight of these fish is carried out using two pairs of bearing planes: they have enlarged not only the pectoral, but also the pelvic fins, and at the fry stages of development, both of them have approximately the same area. Both directions in the evolution of flight led to the formation of specialized forms well adapted to life in the epipelagic.In addition to the development of "wings", adaptation to flight was reflected in flying fish in the structure of the caudal fin, the rays of which are rigidly connected to each other, and the lower lobe is very large in comparison with the upper, in the unusual development of the swim bladder, which continues under the spine to the very tail, and in a number of other features. The flight of "four-winged" flying fish reaches the greatest range and duration. Having developed a significant speed in the water (about 30 km / h), such a fish jumps out to the surface of the sea and for some time, sometimes not for long, glides along it with spread pectoral fins-wings, vigorously accelerating movement by vibrations of the lower blade of the tail fin immersed in the water and increasing the speed to 60-65 km / h. Then the fish breaks away from the water and, opening the pelvic fins, plans over its surface. In some cases, when flying, a flying fish sometimes touches the water with its tail and, vibrating with it, gains additional speed. The number of such touches can reach three to four, and in this case, the duration of the flight, naturally, increases. Usually a flying fish is in the air for no more than 10 seconds. and flies several tens of meters during this time, but sometimes the flight duration increases to 30 seconds, and its range reaches 200 and even 400 m. Apparently, the flight duration depends on atmospheric conditions, since in the presence of a weak wind or ascending air currents ... flying fish fly long distances and stay in flight longer.

Flying fish (from top to bottom): Fodiator acutus, Parexocoetus brachyp-terus, Exocoetus volitans ("dipteran" flying fish), and H. speculiger ("four-winged" swallow fish).

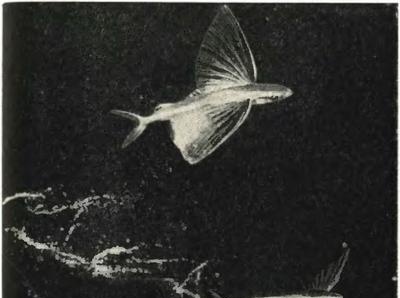

Many sailors and travelers, observing the flying fish from the deck of the ship, claimed that they "clearly saw that the fish flapped its wings just like a dragonfly or a bird." In fact, the "wings" of flying fish remain almost motionless during flight and do not perform any flapping. Only the angle of inclination of the fins can, apparently, arbitrarily change, and this allows the fish to slightly change the direction of flight. The trembling of the fins, which is noticeable to the observer, in all likelihood, is only a consequence of the flight, but not at all its cause. It is explained by a simple vibration of the spread "wings", which is especially strong in those moments when the fish, already in the air, still continues to work in the water with its tail fin.

While studying the flying fishes of the Atlantic Ocean, the famous Danish ichthyologist Anton Brun (AF Bruun. Flying fishes (Exo-coetidae) of the Atlantic, "Dana Report", 1935, No. 6.) first noticed that this group, which was always considered characteristic of the open ocean, contains not only oceanic, but also neritic (coastal) forms. Brun also noted that the family includes tropical ("equatorial", in his terminology) species that are not found outside the tropical zone itself, and subtropical species that live only at the edges of this zone. In his opinion, the temperature of the surface water layers is the factor limiting the spread of flying fish. Further study of the ecology of this group showed that the division of flying fish into oceanic and neritic groups somewhat simplifies the actual situation. In addition to purely neritic species and species confined to open waters, there is also a pseudo-oceanic, or neritic-oceanic, group of species that are found far from the coast only during some period of their life cycle.

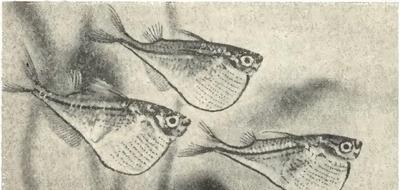

The division of flying fish into these groups is determined by ecological differences. Neritic species usually breed by laying adhering eggs on a hard substrate (algae, bottom). Typical representatives of this group include Fodiator acutus, Parexocoetus mento, some representatives of the genus Cypselurus and a number of other types. In contrast, oceanic flying fish (all species of the genus Exocoetussome Cheilopogon, Prognichfhys and Hirundichthys) inhabit only open areas, and their eggs either develop in the water column, or are deposited on floating objects that can always be found in the sea (drifting algae, fin, bird feathers). Finally, pseudo-oceanic species (these include the bulk of species belonging mainly to the genus Surselurus and Cheilopogon) can exist in the open ocean, but need a solid coastal substrate for reproduction. The habitats of neritic and oceanic flying fish differ significantly in the balance of the seasonal trophic cycles of the communities inhabiting them. The fact is that in the open waters of the tropical ocean, the production of phytoplankton for a long time is close to being consumed by zooplankton, and the production of subsequent levels is close to being consumed by predators at higher levels of the food system. Therefore, oceanic pelagic communities are among the most balanced in terms of trophic cycles and spatial homogeneity of the distribution of organisms. In contrast to these communities, in neritic regions, production for a long time exceeds grazing, and the biocenoses inhabiting them are not balanced in terms of trophism. Pelagic animals are distributed very unevenly here due to the "spotted" algal blooms and form schools and schools.

All flying fish are stenothermal, that is, they live in a fairly narrow temperature range, constant for each species. They are more or less thermophilic, and most of the species do not occur or hardly occur at water temperatures below 23 °. These species constitute a tropical grouping. Only many members of the family have adapted to life in subtropical waters at temperatures of 18–20 ° and below, and in summer they penetrate even into temperate regions; the minimum temperature at which the most "cold-resistant" species was encountered - Hirundichfhys rondeletii, is only 15.5 °. The subtropical group includes only 6-7 species of flying fish (ie, only about 10% of all species of the family). In subtropical waters, only highly specialized flying fish are found, while representatives of the primitive genera Fodiafor and Regehosoetus live only in the tropical zone.

The geographical distribution of neritic and neritic-oceanic flying fishes is completely subject to all the laws governing the distribution of tropical coastal fish in general. An obstacle to their settlement is not only continental barriers, but also open water spaces, in particular, the "East Pacific faunistic barrier" - an island-free region of the Pacific Ocean, between the shores of America and the extreme eastern archipelagos of Polynesia. It is this reason that explains the significant difference in the faunas of flying fish in the western and eastern parts of the Pacific Ocean. The ranges of neritic species, as a rule, are relatively small due to the diversity of ecological conditions near the coast, and among them there are often very narrow endemics living in very limited areas. The factors limiting the distribution of these fish along the coast are the water temperature, its salinity (almost all species avoid freshened areas), the feeding capacity of the regions and, probably, also the nature of the bottom and the presence of vegetation in the coastal zone. Examples of this kind are quite numerous: there are species endemic for the waters of South Japan and Korea, for the waters of Indonesia and adjacent regions, for the Pacific waters of Central America, etc. The subtropical species, the giant flying fish, is very interesting. Cheilopogon pinnati barbatus, up to 50 cm long, inhabiting the coastal waters of Japan, California, Northwest Africa and Spain in the Northern Hemisphere and in the waters of Chile, New Zealand, South Australia and South Africa in the south. The range of this species shows a remarkable similarity with the area of distribution of sardines from the genera Sardine and Sardinops... The distribution interrupted in the tropical zone is also characteristic of such flying fish as Ch. heterurus and Ch. agoo... The concept of bipolarity is quite applicable to the ranges of all these species (bipolarity here means the distribution of animals in temperate or subtropical waters of the Northern and Southern hemispheres in the absence of them in the tropical zone proper) if it is considered in a somewhat broader sense than did L.S. Berg , who noted in his time that organisms of temperate latitudes are bipolar. Now there are many examples of "bipolar" (or, in the terminology of American authors, "antitropical") spread in subtropical animals.

Oceanic flying fish, as a rule, have very extended, often even circumglobal, ranges, and their distribution is most likely determined by only one temperature of the surface water layer. Some species have a very narrow range of optimal temperatures and therefore they are found only in the warmest or, on the contrary, in the less heated waters of the tropical zone. These species include, for example, the Pacific population of the species E. volitans, found here at a temperature of 22-29 °, but the most common at 24-28 °. As a result, the area of distribution of this fish in the warmest western part of the Pacific Ocean is interrupted in the near-equatorial zone at about 15 ° latitude, and in the central and eastern parts of the ocean, where in the equator the temperature in the surface layer is lowered due to the rise of deep waters, such a break no. Inhabiting the southern periphery of the tropical zone proper in the Pacific Ocean E. obfusirosfris has especially narrow temperature limits of distribution in the southeastern part of its range. As the results of the 4th voyage of the research vessel Akademik Kurchatov show, this flying fish is caught only in a narrow strip of waters bounded by isotherms of 19 ° and 22-23 °.

Of particular interest is the distribution of the only subtropical species among the representatives of the oceanic group of flying fish - Hirundichthys rondeletii, which has a bipolar area. This fish is apparently characterized by seasonal migrations: in the northwestern Pacific, spawning occurs in winter between 21 ° and 30 ° N. sh. at a water temperature of 18-23 °, in the spring begins movement to the north for fattening (at this time fish are found at a temperature of 15-17 °), and in the fall - a reverse migration to the southern part of the range.

The quantitative distribution of flying fish within the occupied area is determined primarily by the amount of food available, namely the abundance of zooplankton in the surface layer of the ocean. In this regard, the distribution of flying fish in different parts of the tropical region is highly heterogeneous. Areas of the open ocean, characterized by the largest concentrations of flying fish, are located, as a rule, near zones of divergence, where deep waters rich in biogenic salts rise to the surface, and an increased biological productivity is noted. In this case, the highest concentration of flying fish is usually observed at some distance from the divergences. The fact is that the peaks of the number of each subsequent Even in the trophic chain (phytoplankton -> herbivorous zooplankton -> predatory plankton -> - planktophagous fish) are somewhat shifted downstream relative to the maximum number of the previous link. That is why increased concentrations of flying fish in open waters are sometimes observed even hundreds of miles downstream of phytoplankton accumulations at divergences.

Before taking off into the air, the "four-winged" flying fish glides along the water surface, accelerating its movement with no.voufbio vibrations of the tail fin remaining in the water, and then breaks off the surface and glides, flying tens and even hundreds of meters.

The total number of flying fish in the oceans is very significant. According to V.P.Shuntov, their stock only in the Pacific Ocean is measured in the order of 1.5-4 million tons, which is about 20-40 kg for each square kilometer of the entire tropical part of this ocean. These figures were calculated based on the results of visual counts of fish flying out from under the stem of many ships in various areas, and, apparently, can be attributed to the entire World Ocean.

The number of species of flying fish in different regions of the ocean varies significantly, mainly due to the difference in the number of neritic and pseudo-oceanic species. There are especially many species in the waters of Indonesia (27) and in the adjacent regions of the Coral Sea (26), off the Philippine Islands (at least 21) and southern Japan (25). It is here - in the western tropical part of the Pacific Ocean - that the modern geographic center of the range of flying fish is located and, apparently, also the initial center of the formation of this group.

Comparison of the flying fish fauna of different parts of the World Ocean reveals significant differences. The richest and most varied fauna of flying fish in the Pacific Ocean, where there are 47 species and subspecies. In the Indian Ocean, only 26 species have been found so far, and in the most thoroughly studied Atlantic Ocean - only 16. Each ocean has its own endemic species, the number of which, however, differs markedly. There are 16 endemic species in the Pacific Ocean, 4 endemic species in the Indian and Atlantic ones.

It should be noted that all species endemic to the Atlantic are represented in the Pacific and Indian Oceans by very similar forms. At the same time, many groups of species are completely absent here, uniting in special subgenera and common in other oceans. In general, the flying fish fauna of the Atlantic Ocean is highly depleted (mainly due to specialized species of the subfamily Cypselurinae, the Indo-Pacific flying fish fauna).

Flying fish of the Indian Ocean and the western part of the Pacific Ocean are part of a single faunal group. Differences in the species composition of flying fish in different regions of the tropical Indo-West Pacific are explained mainly by the existence of narrow-localized species occupying limited ranges. This fauna is the most diverse and complete in relation to the genera and subgenera represented in it (only the genus Fodiafor).

The flying fish fauna of the eastern Pacific is very specific. It includes no more than 20 species, including 9 endemic species and subspecies. This fauna is related to the Atlantic Ocean by the genus Fodiator, but in general it seems to be more akin to the Indo-West-pacific complex.

Thus, three main geographical groups of flying fish can be distinguished, inhabiting the Indo-Pacific, East Pacific, and Atlantic faunal regions, respectively. It can be assumed that the original forms of flying fish arose in the Paleocene or Eocene from ancestors close to modern semi-snails (family Hemirhamphidae) in warm-water neritic regions that existed for a historically long period on the border of the Pacific and Indian oceans. The dispersal of flying fish from this center occurred, apparently, in all directions (but mainly to the west), although its path is still not clear enough.

Apparently, the Tethys Ocean played an important role in this dispersal, through which the primitive tropical elements penetrated into the Atlantic along with other thermophilic elements. Exocoetidae... Flying fish undoubtedly migrated through the Panama Strait, which remained open until the Pliocene - only this can explain the modern distribution of the genus Fodiafor on both shores of Central America. The dispersal of relatively "cold-loving" subtropical fish took place, apparently, much later under climatic conditions close to modern ones, and the formation of bipolar areas in them, following the theory of L. S. Berg, can be fully explained by changes in the temperature regime of the ocean during the Ice Age.

N.V. Parin

|

Flying fishes (family Exocoetidae), well known to everyone from the descriptions of sea voyages, are an integral part of the landscape of warm seas and are one of its most characteristic external manifestations.

Flying fishes (family Exocoetidae), well known to everyone from the descriptions of sea voyages, are an integral part of the landscape of warm seas and are one of its most characteristic external manifestations.